Beyond the Barrel

Kentucky’s first female master distiller, Marianne Eaves, crafts a Bourbon sensation

By M. Linda Lee | PHOTOGRAPHY BY PAUL MEHAFFEY

IT’S A MATTER OF DEBATE as to who was the first distiller of corn-based whiskey in Kentucky in the late 1700s. Was it fiery preacher Elijah Craig? Welsh immigrant Evan Williams? Both are often credited with the title, but according to historians, neither claim can be substantiated. One thing, however, is certain: the first distiller of bourbon whiskey—declared by Congress in 1964 as “a distinctive product of the United States”—was a man.

And so it was for centuries that men dominated whiskey production in Kentucky, which produces 95 percent of the world’s bourbon. It wasn’t until 1974 that a state law prohibiting women from working in the industry was repealed. Even so, it stated that a “Female may be employed only as waitress, cashier or usher.” Happily, women have shaken things up over the past 50 years. Just ask Marianne Eaves, Kentucky’s first female master distiller since Prohibition.

Making whiskey was never on her radar as a student at the University of Louisville, until she interviewed for an internship at Brown-Forman, the company that produces Old Forester, Jack Daniel’s, and Woodford Reserve bourbons, among other spirits. From that internship in the research-and-development department, Eaves landed her “first big-girl job” with Brown-Forman after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering.

“It was an incredible company to work for,” she says, noting Brown-Forman’s ethos of diversity. “It’s hard to imagine a better opportunity for me being a young female than to be behind the scenes, learning all the ins and outs that go on in distilleries.”

MAKING HER MARK

Turns out, the technical process of making bourbon fell squarely into her skill set. Until the 1950s and ’60s, when distilleries began hiring chemists, “Everybody was just kind of touchy-feely, making bourbon the way their granddaddy taught them,” notes Eaves. These days, science has inserted itself into the process. “Making bourbon uses every major unit operation that I learned in my chemical engineering curriculum, from fluid dynamics to distillation.” And it doesn’t hurt that she has an exceptional palate.

“It wasn’t until 1974 that a state law prohibiting women from working in the industry was repealed. Even so, it stated that a ‘Female may be employed only as waitress, cashier or usher.’”

As a woman, she brings a different perspective. “I tend to look at things differently than most engineers,” Eaves shares. Although she’s always loved science and math, she also considered more creative career paths, including interior design, at one point. Seeing things through that different lens led her to ask “revolutionary” questions like, “‘I understand that things have been done this way for a long time, but why?’” To which her colleagues replied: “‘You know what, Marianne, nobody’s ever asked.’”

After six years at Brown-Forman, she accepted a job at craft distillery Castle & Key in Frankfort, Kentucky, with the title of master distiller. When asked if that was her goal, she laughs. “No! Until I started training with Chris at Old Forester [Chris Moore, a member of the Kentucky Bourbon Hall of Fame, was then master distiller for the Old Forester brand], I had no idea that was even a possibility for me. I’d never seen another woman doing that job.”

As the one who is ultimately responsible for the quality of the product in the bottle, Eaves sees her role of master distiller as a blend of production and marketing. Not only is she tasked with upholding the quality of the company’s bourbon, but she also goes out into the market to tell people about the brand. At Castle & Key, she was creating a new legacy, based on that of Old Taylor, a brand that dates back to the nineteenth century. “I had the Herculean task of resurrecting a defunct bourbon icon while installing new process equipment and defining new ways to make this unique product alongside equipment that had been sitting there for 50 years. It was like being a master distiller on steroids.”

TAKING A SHOT

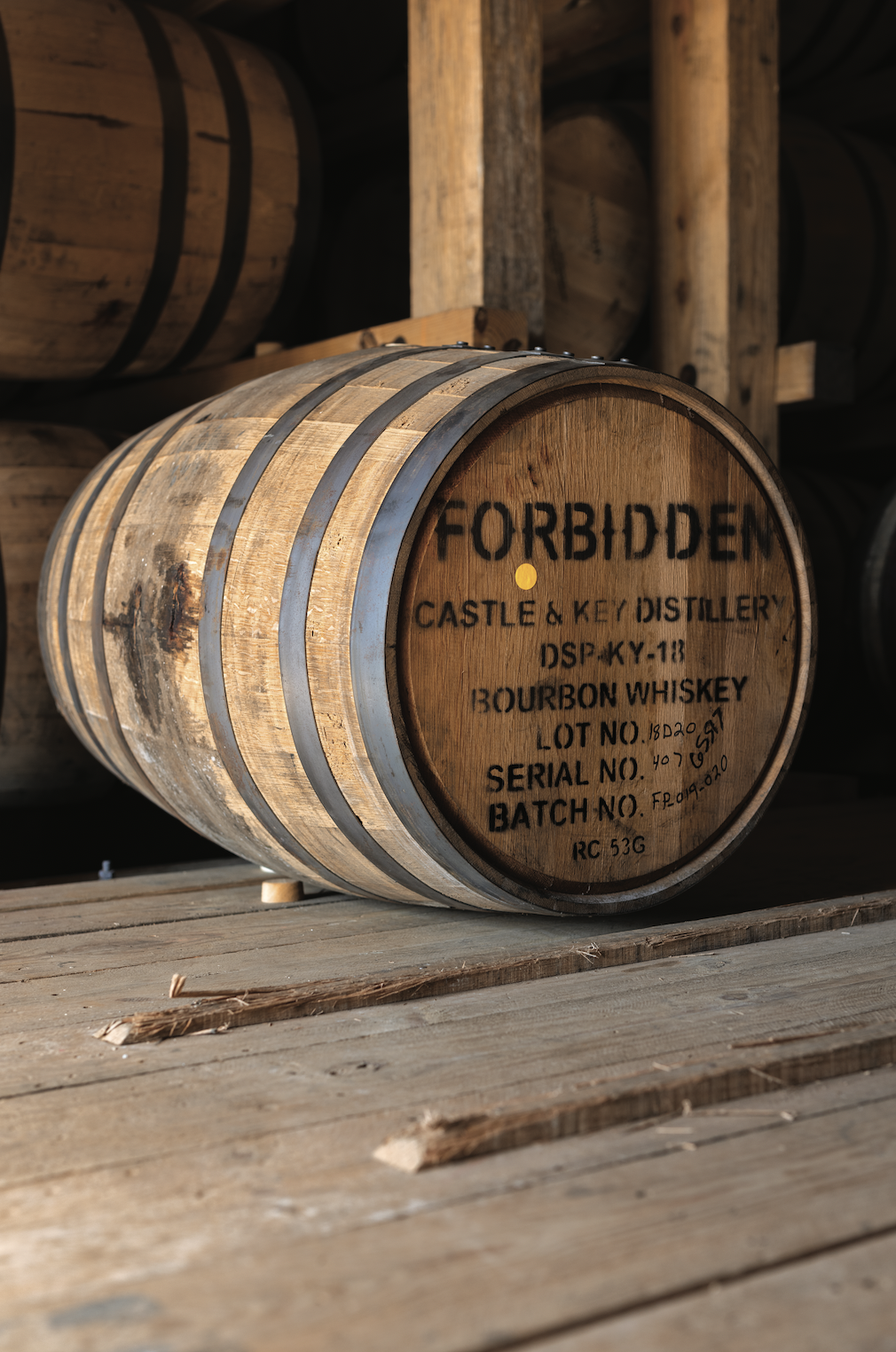

While at Castle & Key, Daniel Rickenmann (now mayor of Columbia, South Carolina), reached out to her regarding a bourbon he and his partners in South Carolina wanted to produce. Castle & Key agreed to make the spirit, and in 2016, Eaves began working on the recipe for Forbidden Bourbon.

In the course of her research, Eaves consulted bourbon-production textbooks from the early 1900s, and her interest was piqued by some of the distilling methods that have been lost to history. Given the freedom to do her own thing, she experimented with variables including lower-fermentation temperatures. “Instead of 80 degrees, if you set the fermenter at 65 degrees, it takes it longer to ramp up, and the yeasts have more time to make flavor before they start making alcohol . . . . It takes longer to ferment, but you come out with different, and I think better, flavors at the end of it,” she explains.

Forbidden’s unique mash bill, the only one of its kind to have been created as an intentional brand, distinguishes the bourbon. By regulation, to be called “bourbon,” a spirit must be at least 51 percent corn. Eaves chose sweet white corn, a summer staple in the South, to compose 75 percent of Forbidden’s mash. To that, she added 12 percent white wheat, and 13 percent malted barley, resulting in a remarkably smooth finished product with a creamy, sweet profile.

Eaves loves to say Forbidden is inspired by Southern food traditions, as it’s full of buttery and creamy notes reminiscent of biscuits and gravy. “I strive for balance and complexity, so there’s some unique citrus and fruit notes in there, too,” the distiller adds. “You’ll also taste some toasted, caramelized oak. It’s very complex.”

The first runs of Forbidden Bourbon were made in 2018 and aged for five years in oak. Eaves and her three business partners have plans for a second run, and even a cask-strength expression of their bourbon. As the first product she made for somebody else while working at Castle & Key, Forbidden pushed the master distiller out of her comfort zone. Forsaking the recipes she’d used in the past, Eaves realized that—unlike every Kentucky distiller who thinks their way is the best way to make bourbon—there are infinite ways to make great bourbon. “The high altitude in Colorado does something different; the extreme temperatures in Texas have something to contribute; the salinity in the air in Florida has something to contribute,” she muses. “It’s interesting to consider all of those variables, and I think we’re just getting started.”

Beginning with her first job at Brown-Forman, Eaves has been instrumental in changing the face of the whiskey industry. Now operating under her own LLC, launching Forbidden and consulting for other brands, she’s proud of what she’s accomplished and grateful for the doors that were opened to her.

“As a millennial female distiller, people have always had me under a microscope, and so I’m proud to have been able to weather that and come out and still produce excellent quality [products],” Eaves says, adding that she’s been gratified by the number of women who have come forward to thank her for showing them what’s possible. “Hopefully, being a woman building a distillery of my own in the near future, I want to be the one opening those doors.”

You can currently find Forbidden Bourbon online at Bourbon Outfitter and in liquor stores throughout South Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, and georgia; drinkforbidden.com

more women in whiskey

These enterprising women have redefined the distilling industry.

High Wire Distilling | Charleston, SC

The distillery that marketing maven Ann Marshall founded with her husband, Scott Blackwell, 10 years ago focuses on producing small-batch, regionally based products. James Beard Award finalists in 2020, Marshall and Blackwell revive a sense of place in High Wire’s signature Jimmy Red Bourbon, made with an heirloom variety of South Carolina corn. highwiredistilling.squarespace.com

Chemist Spirits | Asheville, NC

After four years of home-distilling experiments, landscape architect Debbie Word launched Chemist Spirits in 2018 with her daughter, Danielle Donaldson—a chemist by degree. Owners of one of the few female-founded distilleries in the country, Word and Donaldson have won multiple awards for their balanced botanical gin, crafted using locally sourced botanicals, as well as their limited-edition single malt whiskey. chemistspirits.com

Uncle Nearest | Shelbyville, TN

Founder and CEO of Uncle Nearest Premium Whiskey, Fawn Weaver purchased the 300-acre farm in Lynchburg, Tennessee, where Nathan “Nearest” Green—who became the first known African American master distiller—taught a young Jack Daniel the art of making whiskey. As senior vice president for sales and marketing for Uncle Nearest, Katharine Jerkens has led the brand to become the fastest-growing independent American whiskey brand in history. And bourbon runs in the bloodline of Uncle Nearest’s master blender, Victoria Eady Butler. The great-great granddaughter of Nathan “Nearest” Green, Butler reigns as the first African American female master blender in America. unclenearest.com

Maker’s Mark | Loretto, KY

As the wife of T.W. “Bill” Samuels Sr., Margie Samuels (1916–1985) made enduring contributions to her husband’s company, Maker’s Mark. The daughter of a whiskey distiller in Louisville and the first woman to be inducted into the Kentucky Bourbon Hall of Fame, Samuels created the brand’s distinctive bottle design and trademark red wax seal that drips down the bottle’s neck. makersmark.com